our water story

The Era of Free Flowing Water

Time immemorial to 1862

Since time immemorial, the Paiute and Shoshone have lived in Payahuunadü, stewarding the land and water. To the north, the Kootzaduka’a have always lived near what is now called Mono Lake and Yosemite. The Paiute developed agricultural practices that included the creation of irrigation ditches to spread water and grow native food species. This also provided a way for them to easily harvest fish from the streams. For millennia, the Paiute and Shoshone lived by taking care of the waters of the valley until settlers and colonial ideas of ownership and management disrupted the Indigenous way of life.

When the water flowed freely, Payahuunadü had vast alkali meadows, a unique ecosystem supported by the naturally shallow groundwater table. Alkali meadow is a groundwater dependent ecosystem, meaning that it requires the water table to be at a level where plant roots can absorb water and thrive.

The Era of Dividing Land and Water

(1862 to 1920)

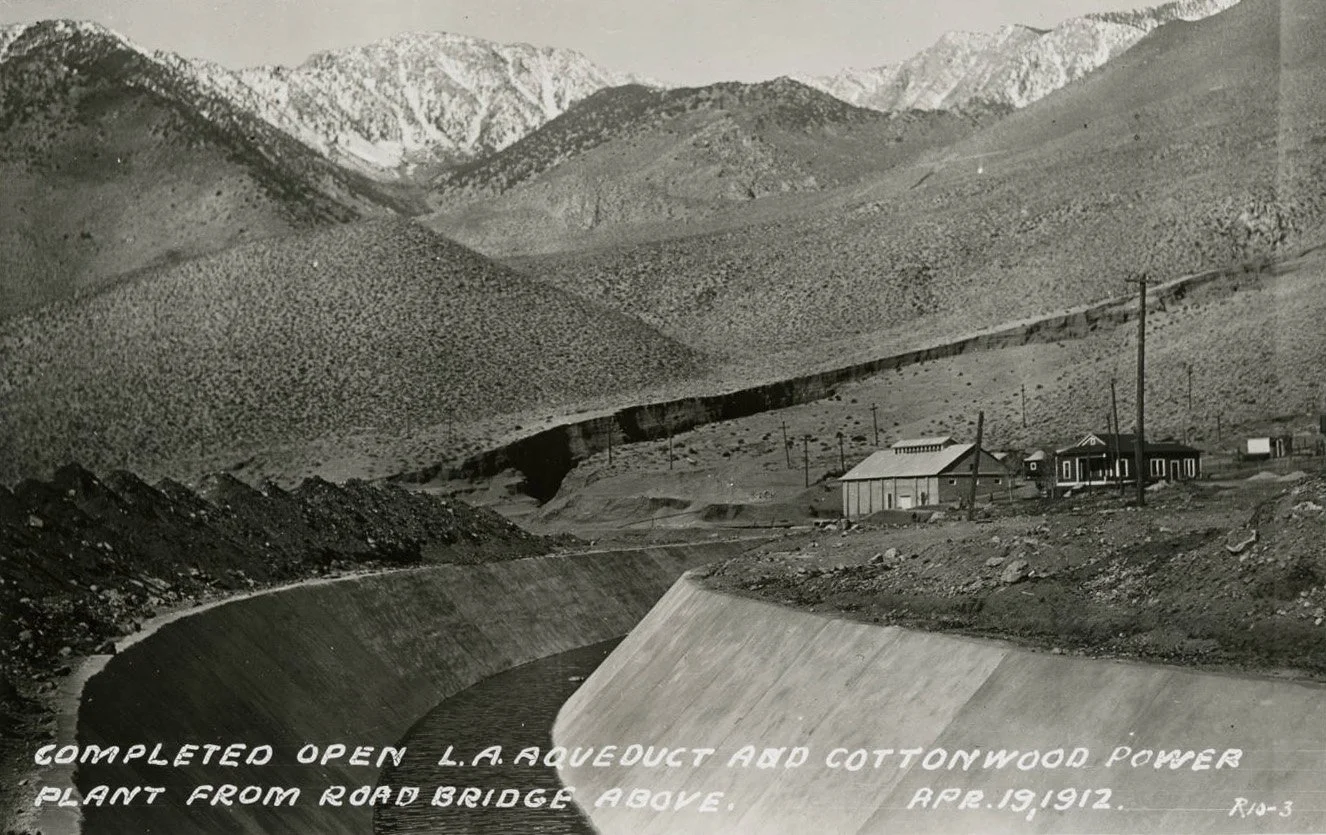

Payahuunadü was uniquely insulated from the influx of settlers who came to California for the gold rush, due to the region’s isolation. But starting with the 1851 California Land Act and 1862 Federal Homestead Act, a series of government policies would enable settlers to claim lands and fundamentally change the way of life in the valley. The Paiute and Shoshone were displaced from both their lands and their way of life, and a series of violent conflicts occurred between the Indigenous people and settlers, including an attempt at Indigenous removal during the 1863 forced march to Fort Tejon. Even after this forced removal, the Paiute and Shoshone were determined to stay in the valley, though their ability to live on their homelands was continually challenged by racist policies, forced assimilation, and disruptions to their traditional way of life.

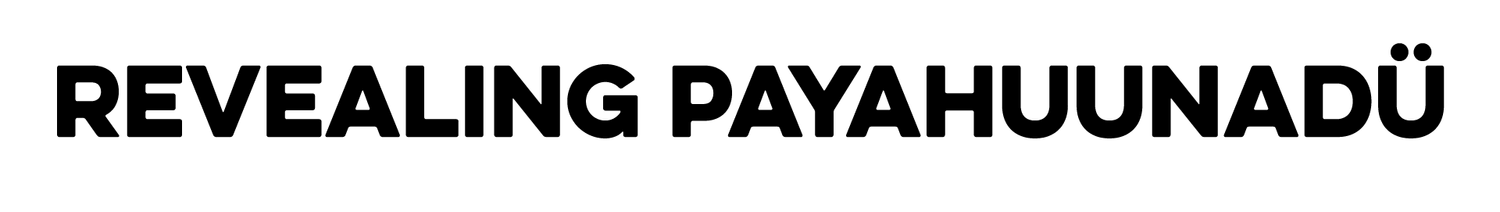

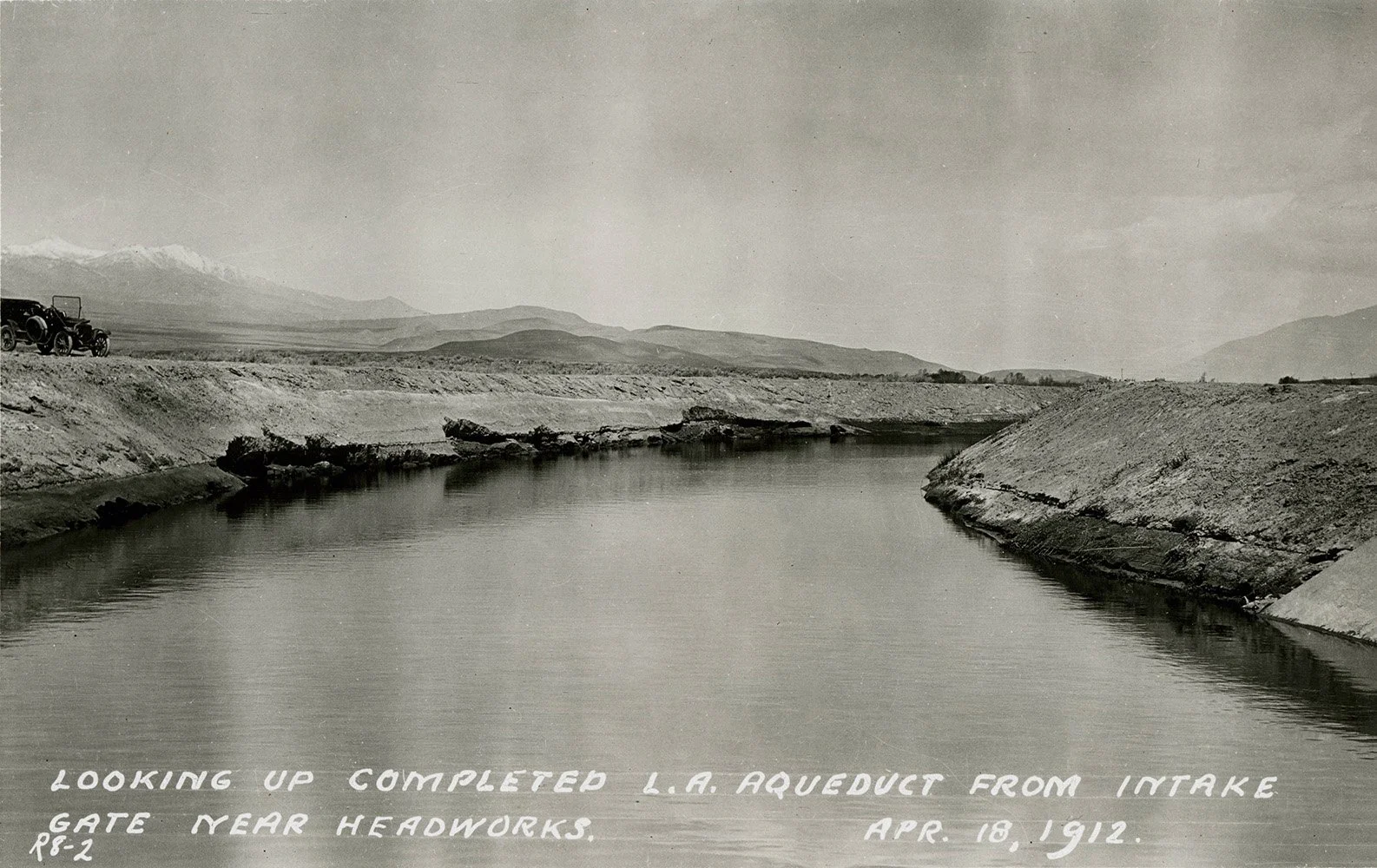

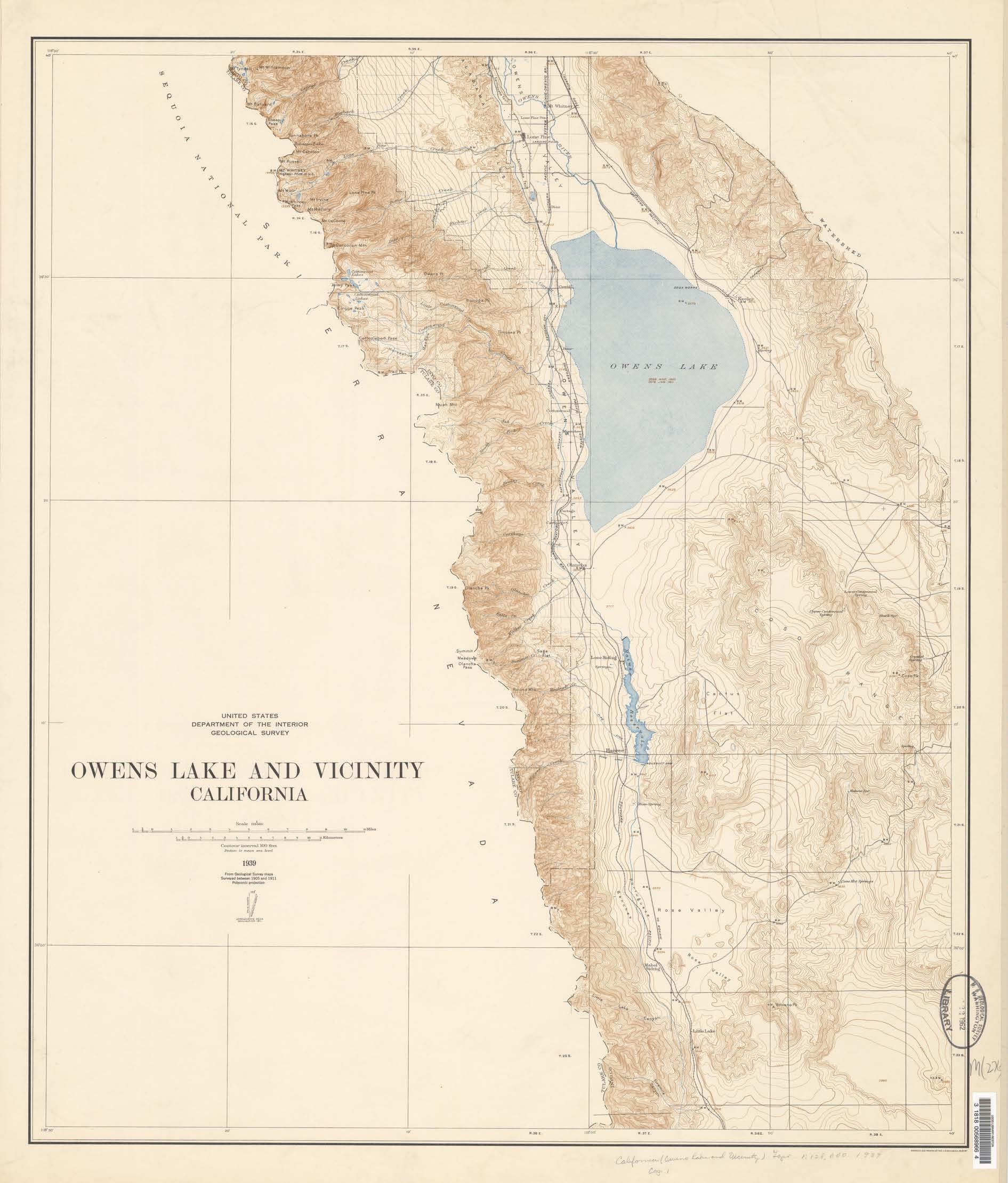

Starting in 1905, the City of Los Angeles began to buy property along the Owens River and other lands that held water rights. During this period, the federal government withdrew lands from the public domain, in part to ensure that LA would be able to purchase the lands it needed for the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This left fewer lands available in the valley for private settlement, including by the Paiute and Shoshone people who were encouraged to claim lands through the allotment process. By the time the Aqueduct was completed in 1913, LA owned 82,000 acres and was able to divert 300,000 acre-feet per year from the Owens watershed. The last 50 miles of the Owens River and Owens Lake were completely dry by 1924 as a result of the Aqueduct.

The Era of Increasing Water Extraction

(1920 to 1970)

In the 1920s, LA sought to increase its available water supply from Payahuunadü. This included purchasing more land further north in the valley, drilling wells, and filing claims to water rights on Mono Basin streams. During this period, the local communities protested against the impacts of LA’s land and water grab, including the economic decline of the valley, and staged an occupation at the Alabama Gates (a spillway that allows water to return to the Owens River from the Aqueduct). By 1933, Los Angeles would own 95% of agricultural lands and 85% of town lands in the valley.

In 1930, LADWP released a report describing the “Indian Problem” in the valley and proposing they be able to purchase the remaining Indigenous allotments and homesites in exchange for a consolidated land base. This was followed by a 1932 report that asserted a consolidated land base would only be a temporary “solution” and that the ultimate goal would be removal of the Paiute and Shoshone from the valley within the next 20 years. The 1939 Land Exchange was approved by Congress, designating what is the current land base of the Bishop Paiute Tribe, the Big Pine Paiute Tribe, and the Lone Pine Paiute-Shoshone Tribe. In this exchange, the Tribes would end up with less land and would be unable to claim their water rights, due to Los Angeles claiming that the City Charter limited their ability to transfer water rights without a two-thirds citizen vote. Those tribal water rights remain unresolved to this day.

LADWP expanded its infrastructure north to the Mono Basin with the construction of the Mono Craters Tunnel, enabling diversions from Mono Lake tributaries. This dropped the level of Mono Lake by 45 feet and reduced its volume by half, greatly impacting the ecosystem and creating toxic dust pollution. In 1963, LADWP decided to further increase its water extraction by building a second aqueduct that would carry an additional 200,000 acre-feet per year. The second aqueduct was completed in 1970.

The Era of Legal Resistance

(1970 to 2014)

For the first time, communities in Payahuunadü were able to hold LADWP accountable for its impacts because of violations of policies such as the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) of 1970. Inyo County filed a lawsuit against LADWP on the basis that the effects of their groundwater pumping, which had increased to fill the second aqueduct, had to be analyzed under CEQA. What followed was a series of lawsuits, court decisions, and settlements that define current management practices and institutional relationships.

The 1991 Long Term Water Agreement is the governing groundwater management document, which defines how LADWP and Inyo County work together on an annual basis. A memorandum of understanding (MOU) between LADWP, Inyo County, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Sierra Club, the Owens Valley Committee, and the State Lands Commission was adopted to address the inadequacies of the environmental review process in 1991. This 1997 MOU provides detail on the mitigation projects that LADWP must complete because of the impacts of its groundwater pumping between 1970 and 1990.

The advocacy of local organizations resulted in additional legal action that required LADWP to modify their behavior to reduce or mitigate their impacts on the environment, including restoring the flow through the Owens Gorge, addressing the dust pollution from Owens Drained Lake, and decreasing water exports from Mono Basin.

However, many of these mitigation projects and legal requirements remain unfulfilled or incomplete, and there are limited and ineffective enforcement mechanisms. It is important to note that these legal processes did not require consultation with the Tribes of the Owens Valley, although they had also been adversely affected by LADWP and its management practices for decades. The Owens Valley Indian Water Commission was formed in 1991 and has been working to support tribal sovereignty and water rights in the valley since.

The Era of Coalition Building and Water Justice

(2014 - present)

The past decade has included the building of alliances within Payahuunadü that can lead us to a better water future. Diverse communities, including environmental organizations, tribes, and ranchers, have come together on issues that affect the way of life and the landscape of the valley. The Keep Long Valley Green Coalition (KLVG) formed in 2015, in response to LADWP proposing to cut irrigation water to leases in Long and Little Round Valleys. KLVG won a lawsuit against LADWP, in which a court decided LADWP had to complete environmental review before it permanently altered the provision of water to leases.

Additionally, there have been milestones in state policy that signify changes to the way we work together on managing our resources. Among those changes is Assembly Bill 52, which requires consideration of cultural resources and supports tribal consultation during the CEQA process, though with little accountability to tribal input. Another major state policy was the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which led to the creation of the Owens Valley Groundwater Authority, though LADWP lands (and thus the majority of groundwater pumping) in Inyo County are exempt from management under SGMA.

Recently, the Eastern Sierra Water Alliance formed to bring communities together and advocate for a future with more equitable water management. In 2023, the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission succeeded in the first Land Back initiative in the valley to return land and water to the Indigenous people. They established the Three Creeks Collective, which serves as a place of community healing on 5 acres of land. Water extraction over the past 100+ years has affected many aspects of life, but restoration is possible through stewarding and protecting the water, as the Paiute and Shoshone have done for millennia.

References

“A History of Water Rights and Land Struggles.” Owens Valley Indian Water Commission, 15 Apr. 2025, www.oviwc.org/. Accessed 30 June 2025.

Borgias, Sophia Layser. Public Interest, Indigenous Rights, and The Los Angeles Aqueduct. 2020. The University of Arizona, PhD dissertation.

Borgias, Sophia L. 2024. Drought, Settler Law, and the Los Angeles Aqueduct: The Shifting Political Ecology of Water Scarcity in California’s Eastern Sierra. Journal of Political Ecology, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5448

Borgias, Sophia L. 2024. Denaturalizing Dispossession in the Political Ecology of the American West: Reassessing the History of the Los Angeles Aqueduct and its Implications for Indigenous Land and Water Rights. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 114(6), 1232–1250 https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2024.2332649 [available to read for free online here: https://www.tandfonline.com/share/IUTPXUXS6GNSMFNNTSPA?target=10.1080/24694452.2024.2332649]

Klingler, C.J. & Pritchett, D. “OV water history, LTWA.” Owens Valley Committee, https://owensvalley.org/2-1-ov-water-history-ltwa/. Accessed 30 June 2025.

Lawton, Harry W, et al. “Agriculture Among the Paiute of Owens Valley.” Journal of California Anthropology 3.1 (1976): 13–50. Print.

“Owens Valley Water History (Chronology).” The Inyo County Water Department, Inyo County, Jan. 2008, https://www.inyowater.org/documents/reports/owens-valley-water-history-chronology/. Accessed 30 June 2025.

“Saving Mono Lake.” Mono Lake Committee, 28 Jan. 2025, www.monolake.org/learn/aboutmonolake/savingmonolake/. Accessed 30 June 2025

Superior Court of California, County of Inyo. Agreement Between the County of Inyo and the City of Los Angeles and Its Department of Water and Power on a Long Term Groundwater Management Plan for Owens Valley and Inyo County, 1991. Inyo/LA Long Term Water Agreement, Inyo County Water Department. https://www.inyowater.org/documents/governing-documents/water-agreement/#AGREEMENT.