1863

The Forced March to Fort Tejon attempts to remove the Paiute and Shoshone from the valley. One thousand Paiute and Shoshone are forced to march for 12 days, with 250 individuals dying along the way. About 200 Paiute-Shoshone people end up escaping along the march or from Fort Tejon, returning to Payahuunadü.

With agriculture and other industries, such as mining, expanding in the mid to late 1800s, the Paiute serve an important role in the regional economy by providing vital wage labor. Settlers even protest a potential 1873 plan for the Indigenous community to be relocated to the Tule River Indian Reservation because of the work force they provide.

“Their labor is of essential importance in public economy and supplies a want in that direction that no other can do as well.” - From the Inyo Independent on August 22, 1985; quoted in Walton 1991.

-

1875

Indigenous individuals are granted the right to establish homesteads on the public domain, more than a decade after it was opened to settlers. At least twenty were established between 1875 and 1900, despite discrimination and bureaucratic hurdles.

-

1902

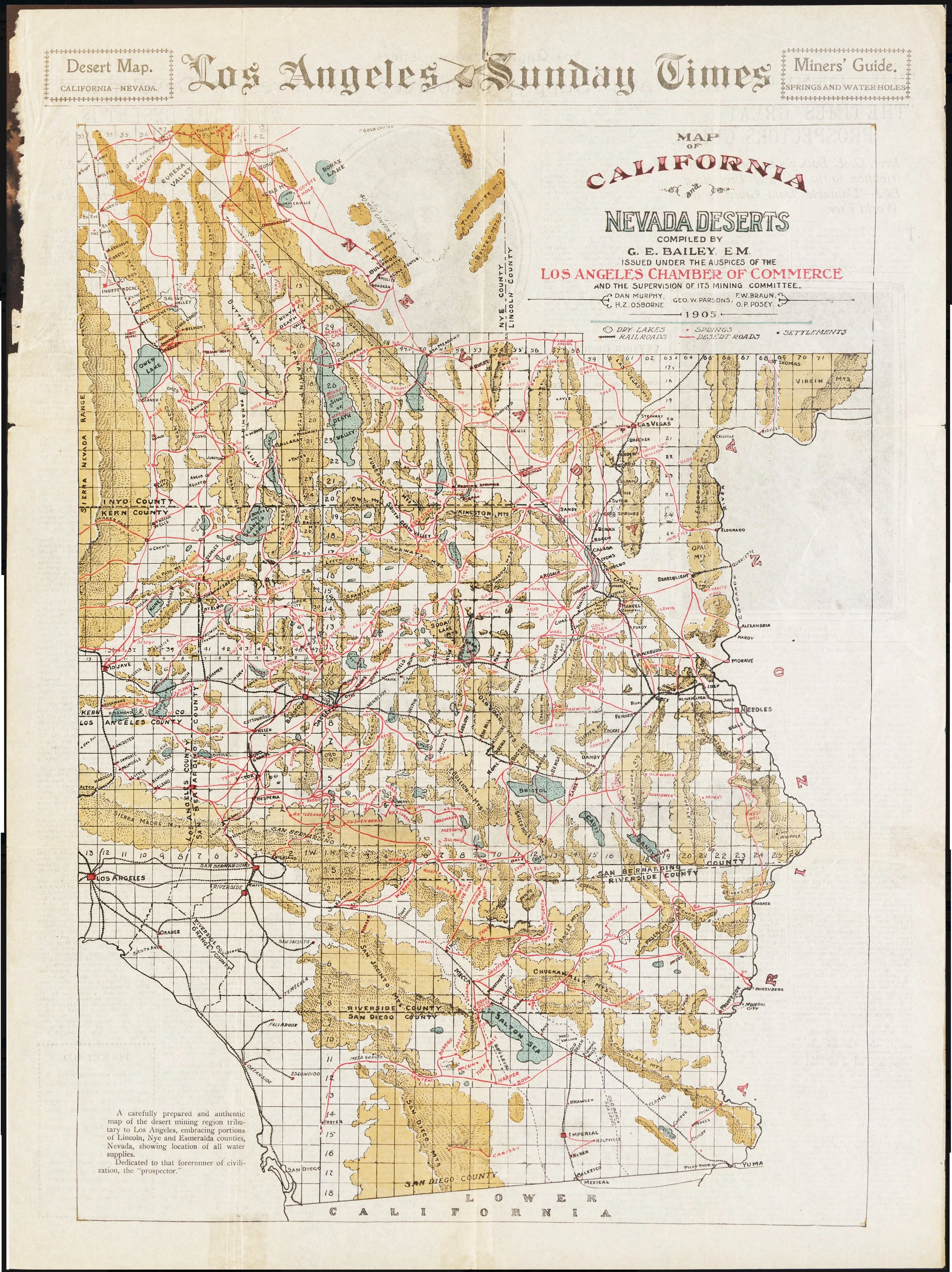

The newly formed Bureau of Reclamation begins planning a public irrigation project for Owens Valley around the same time that Los Angeles officials also begin dreaming up plans for an aqueduct. When they learn of this, federal officials ease up on their plans and share data to aid in the city’s planning.

-

1905

Working on behalf of Los Angeles, Fred Eaton purchases all private lands within potential reservoir sites and along the lower 62 miles of the Owens River. LA files claims on 1,250 cubic feet per second of water in the Lower Owens River.

1906

A bill is introduced to allow Los Angeles to purchase federal land necessary for the aqueduct right of way. President Roosevelt endorses it, claiming the water is “more valuable to the people as a whole if used by the city than if used by the people of the Owens Valley.”

1909

By this time, Los Angeles has claimed ownership of 82,000 acres in the valley.

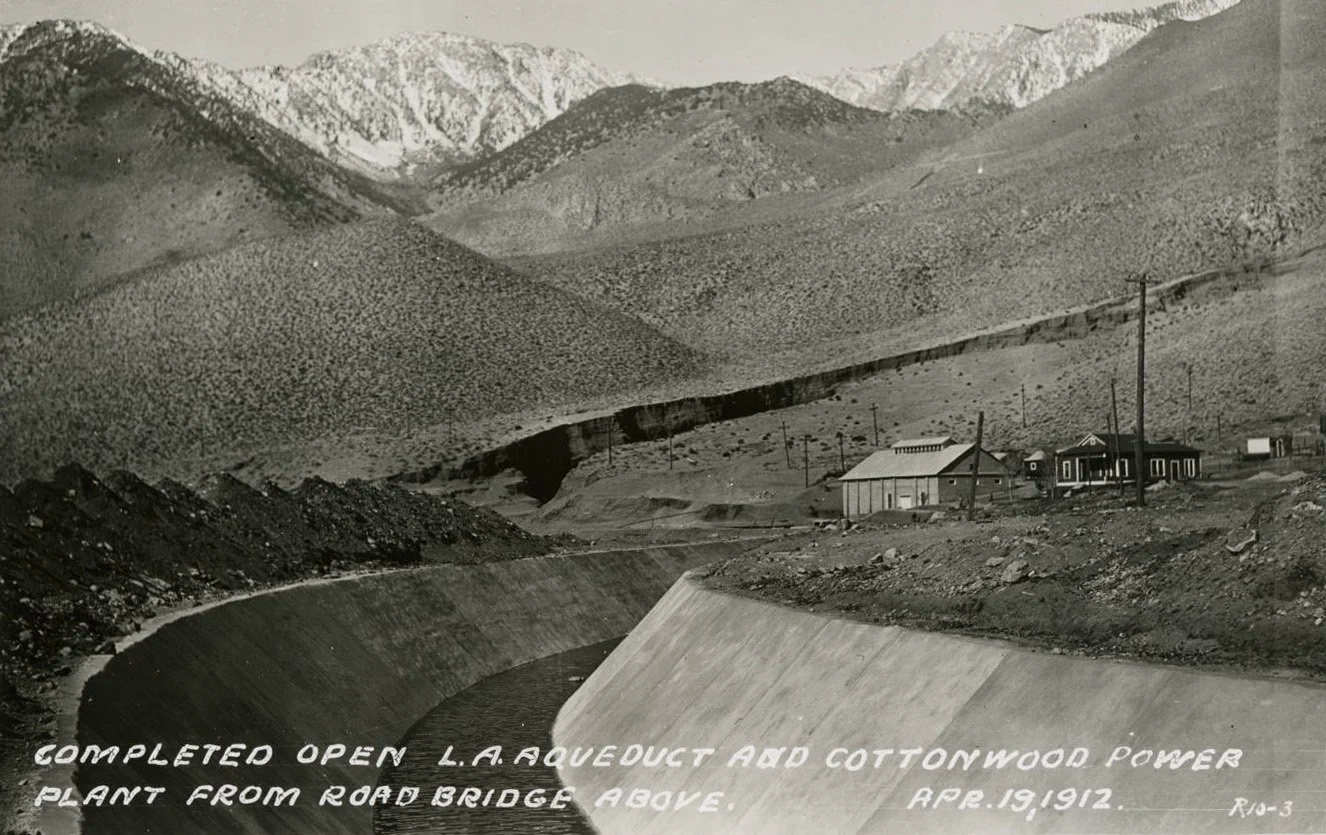

1912

More than 67,000 acres on the volcanic tablelands are reserved by executive order for Indigenous use. However, these lands will never be utilized as a reservation and are removed from federal trust for reasons related to water availability in 1932. Another 2,800 acres are reserved for Indigenous use that would later be traded to Los Angeles.

An Acre-foot is the most common unit of measurement for water, though there are other measurements like miner’s inch and cubic feet per second. One acre-foot is the volume equivalent to a football field (minus the endzones) full of one foot of water. It is equal to 43,560 cubic feet or 325,851 gallons.

Image courtesy of USGS

how much is a acre-foot?

1914

The State Water Commission is formed, which recognizes and issues water rights permits. Multiple adjudications in various creeks occur that start to formalize water rights.

An adjudication is the legal process by which water rights are defined for users with claims within the same watershed. Soon after the State Water Commission (now the State Water Resources Control Board) is formed, adjudications take place for Lee Vining Creek, Rush Creek, Taboose Creek, Big Pine Creek, and Baker Creek.

In these adjudications, a pattern emerges of non-Indigenous users, including Los Angeles, receiving more water rights than neighboring Indigenous users. In many instances, private landowners with water rights would later sell their land to Los Angeles.

REFLECTION

What is something new you learned about this water era?

Is there something you think is important about this time period that is not included in the timeline?